Named James H. Coffman, I was born in Sibley Hospital, Washington, DC on January 31, 1943, and raised in Maryland, and currently live in the State of Maryland.

In 1959, when I was sixteen-years-old, I was first introduced to karate by a guy that was dating my older sister Lois. Ski was stationed at the Navy station in Maryland. Ski told me he learned karate while stationed in Japan. He was teaching me blocks, kicks, and punches, basic street techniques. Once I was exposed to real karate for myself, I found out just how little Ski really knew. It all started when I went into the Air Force. I was assigned to Lackland, Air Force Base, San Antonio, Texas for boot camp. I was 17 years young.

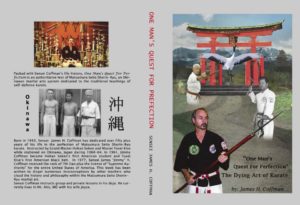

After boot camp, I received my orders, I was to be stationed in Okinawa. By complete luck, I was sent to the very island where karate was born. Fusei Kise (my karate teacher) was at his peak of hard training, he was a Yon-Dan (4th-degree black belt) and in his early twenties. At that time, he was not worried about just making money. He was building his reputation on Okinawa as a hard ass karate-ka. Had I arrived just a few years earlier there may have been apprehension about teaching an American, had it been a few years later I would not have been trained in the pure utilitarian karate I was taught. By 1965 the karate that I learned on Okinawa was fast disappearing, watered-down, and commercialized under the flood of well-heeled American soldiers that would pour in by the tens of thousands during the Vietnam War.

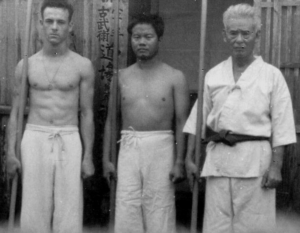

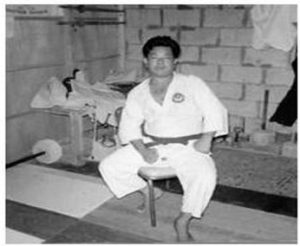

When I first started training with Kise, he had no American students, no cynicism, and no concept of teaching karate for a profit. He was twenty-five years old—close to my own age—a scrappy, rebellious, and very hard conditioned fighter, who knew the most senior karate teachers in the world. He lived for karate in a place and time where there were no lawsuits or worries about getting sued or retaining enough students to pay rent on his dojo. His dojo was a part of his home.

The art he taught and practiced was driven by its street effectiveness, and honed in real—and sometimes violent—fights in and out of the dojo. Kise taught me the same way he taught the Okinawan students in his dojo. For the three and a half years that I would live and trained in Okinawa, I had no distractions—no family, few bills to pay, an easy job—and no preconceived notions about karate from Bruce Lee films, or Kung Fu TV shows.

My first gi (karate uniform) cost three dollars. My lessons at the dojo cost $5.00 per month. A monthly bus pass to and from the dojo was about $2.50. Classes were five dollars a month, seven days a week, and we trained every day. There was no air-conditioning, fans, or heat; none of the amenities we have here in the States.

Once on Okinawa, I was assigned to work as a driver for a small Okinawan, named Fusei Kise. I was a kid with a chip on his shoulder as big as an aircraft carrier. Though I initially treated my new partner with impertinence, I would soon learn Fusei Kise was one of the toughest karate practitioners on the island. Many people think of karate as Japanese, it was an Okinawan named Gichin Funakoshi who first introduced it to Japan in 1922.

The islands of Okinawa are halfway between China and Japan. For hundreds of years, the Okinawan’s played one off the other—trading with both—until samurai warriors from Satsuma in southern Japan invaded, conquered, and subsequently banned all weapons. Kise studied under Shuzen Maeshiro, a Hachi-dan (8th-degree black belt) who learned the craft from a famously small fighter, named Chotoku Kyan (born 1870), who had been instructed by the famous Okinawan Master, Sokon Matsumura. I studied under a direct relative of Sokon (Bushi) Matsumura himself, Hohan Soken, a lineage as pure as they come.

What got me hooked on Karate was when I found out that Kise could break a red brick with his bare hands, I was mesmerized. I asked him to prove to me that he could truly break a brick with only his hands. He complied with my request. I picked up my camera and we drove to the housing area, where I pulled a brick from a garden edging. I watched Kise break a standard red brick with just his hand. From that moment on—from my very first day of work in Okinawa—I became Kise’s puppy.

Kise’s dojo: the building was maybe twenty feet wide by eighteen feet long, plus or minus, with two open windows, and a sliding door to enter. The building served as both Kise’s home and his dojo. It was divided by a wall that ran down the full length, one half his living quarters, and the other half his training dojo.

I remember my first training day, we entered the tiny dojo through a sliding wooden door. I followed the example of my new companions, all young Okinawan boys, ages from about 16 to 20. I took off my shoes before stepping up onto the dojo’s floor. It appeared that Kise had built the dojo himself because the floor was nothing but a bunch of random wooden boards and the walls were an unpainted cinder block. Two bare light bulbs hung from open rafters. Sliding pieces of wood covered windows at each end of the room. On one wall across from the doorway hung a white sign painted with karate techniques. The tops of a few karate uniforms, known as “gi,” lay on the floor.

Kise paired me with the only black belt other than Kise, Miyagi. Even though Miyagi was about my height and age, he was strongly built. I later found out that he was the karate teacher at his local high school. I could already tell he was good. He was the class leader—the tough guy everybody respected. He worked so hard during class that his uniform, pants, and top would become completely soaked with sweat. In later classes, after we started fighting, he would jump up, grab the rafters, and kick me right in the face. After that I set a goal, telling myself: “He’s the one I’m going to beat.” (That day did, in fact, come to be.)

I never heard the currently fashionable word “grappling.” We never caught someone and twisted or locked them, and tried to avoid ending up on the ground at all cost. If you had to catch someone, you hit him at the same time. If you swept him off his feet, you hit first, then hit again as he went down. Kise would always say: “No judo! The same time it takes you to catch, you can hit. Hit, no catch. Hit!”

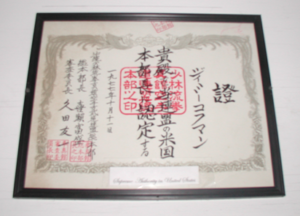

On the 20th day of December 1961, I became Fusei Kise’s “First American black belt” earning my Sho-dan (1st-degree black belt rank). I had been training each and every day, five hours a day. I was completely obsessed with Kise, and his Art.

After I received my Sho-dan, I started training with one of Kise’s teachers, Hohan Soken while continuing my training with Kise.

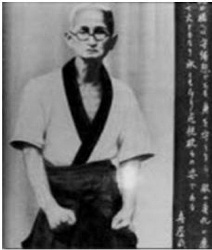

Soken was known as a teacher of teachers, a thin, small man with white hair, he was in his seventy’s at the time. Upon our first meeting, Soken asked: how many days per week do you train? “Seven,” I said, each and every day.

“Well,” he said, “how much are you willing to put into your training?”

“Whatever it takes,” I told him. “I’ll do whatever it takes.” Truthfully, in those days, if Kise had told me to go AWOL, I would have gone AWOL.

He laughed, explaining: “Not everyone who takes karate gets good at karate”. If you’re trained wrong, you can take karate for thirty years and still not be any good. Karate is forever; it’s for your whole life. It’s not for a year or two, and it’s not only twice a week, as most train. At the time, the opportunity to train with Soken didn’t mean anything to me. Now people, as I, cherish any connection at all to Soken, no matter how tenuous. Soken was a great and very revered karate master on the island. I was young and had no knowledge of his advanced skill and what he could teach me. Today, to have trained a day with him, or even to have simply shaken his hand, is considered something like having been in the presence of a karate God. A week later, we took the bus back to Soken’s house right after work—this time with gi, bo, and sai. This is when I became-Hohan Soken’s first American student, 1961. We returned every week thereafter for a couple of hours. But a few weeks after I started training under him, we started working on one-step techniques. Soken would show a technique using Kise as uki, and then oversee Kise and me working together on the technique. That’s when I first started to realize that Soken was special. I knew just how strong Kise was, but Soken could bend him over in pain. Sometimes Kise would jump back and wince after a hit. Even though Soken was mild-mannered, he had a mean streak somewhere deep inside—like all great karate-ka. If he could hurt Kise, I knew he was someone to be respected.

When I reached Fourth Dan in November 1963, Kise gave me eight pages of detailed anatomy charts, which listed targets and explained—in both Japanese and English—how to attack them. I don’t know who originally created them, but they bore Maeshiro’s chop (name stamp), so I know that’s where Kise got them. When we went over the charts, I would point to things and he’d show me how to hit it.

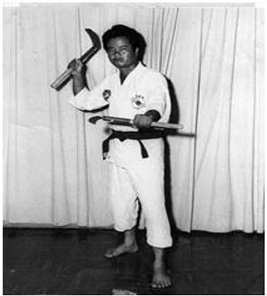

Kise had me wear boguzuki, (protective fighting gear) headgear, and gloves every time we sparred; we occasionally tried to hit each other with weapons, but mostly in the context of drills and one-step self-defense techniques. With a weapon, there aren’t many blows exchanged without causing damage. If any real fight lasts more than a few seconds, you’re doing something wrong, but that’s especially true with a weapon. You can’t strike a person with a razor sharp kama or a sai many times without killing them, or a least doing major damage.

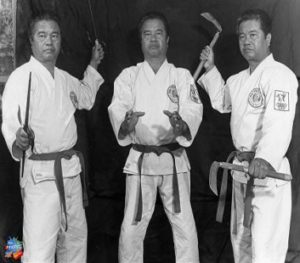

During my training with Kise, he would often take me to visit other dojos on the island to expose me to the various styles. Kise and his students belonged to the All Japan Karate-Do League (AJK) of which Nakamura, Shigeru (1894-1969) was the number one Okinawan representative. Shimabukuru, Zenryu (1908-1969) was second in command. Maishiro, Kise’s instructor, was third in command on the island. He was the Koza city branch official. I had been taken to Grand Master Nakamura’s home in Nago several times, a two to three-hour bus ride from Kadena, as well as fighting at Grand Master Shimabukuru’s dojo, not knowing why we were going.

The first time Kise had me do only kata for the Grand Master, the second time I did kata and fighting. Sensei Nakamura had chosen one of his better fighters, a rank higher than mine. After suiting up in bogozuki (body armor) Kise acting as the referee would stand between us, then look for Nakamura’s approval to start. Next, he would shout “Hajimarimas”, begin, both my opponent and I would start banging on each other, throwing kicks, punches and anything we could throw. After about four to five minutes Kise shouted “sumashimas” finish. Both my opponent and I thought we were the winners. Nakamura said “yoi, yoi”, good, good! It was not too much later that I found out why I had been taken to all of the these different school s fighting and performing kata, as well as to the Grand Master’s home. I had been one of two Americans chosen to represent Okinawa in the Tokyo Championships.

Now I know that all of those trips to Nakamura’s and Shimabuku’s was part of the representation selection process.

All good things finally came to an end in late 1964 when I was twenty-one years old. I’d been in Okinawa for forty-two months, (three and one-half years) training under Kise the whole time, without a break, seven days a week, an average of five hours per day. I was a Fourth Dan by then and was working on Fifth with Sensei Kise and Grand Master Hohan Soken, when I got orders for my return to the States. I was being sent to Pope Air Force Base at Fort Bragg in Fayetteville, North Carolina.

By then, modern developments were already affecting Okinawan karate. When I first arrived on the island in 1960, there hadn’t been a single American training at Kise’s dojo. By the time I left, Kise had sixty-seven +- GIs in his class on base at the Schilling Center dojo, plus another handful at his home dojo.

After I returned to the states I found out that a friend of mine who’d studied Okinawan Kempo under Sheguru Nakamura, Gary Saluter, was living in Maryland (my home State) too, so we started working out together three or four times a week.

Upon returning to Maryland, right away, of course, I started going to every karate school in the area. In those days, there weren’t many: a few Korean schools, a Goju-Ryu school, and an Isshin-Ryu school. I sparred with anyone who would answer my challenge, but I found no impressive karate technique, or dojo’s that I wanted to join. The karate and training were completely different from Okinawa, much softer, lacking the full contact I was used too. Classes were short and less aggressive, students were weak and trained with unrealistic techniques involving little direct contact, plus weapons’ training was rare back in 1965.

I thought that if I opened my own school, I could have hundreds of students by teaching the way Kise had taught me on Okinawa.

In 1965, I opened my first karate school with Gary Saluter. It was located in Washington DC, above a bar, The Rabbits Foot. The training was seven days a week, three to four hours per class. The school lasted less than one year due to the loss of students. We could not keep students because of the hard contact.

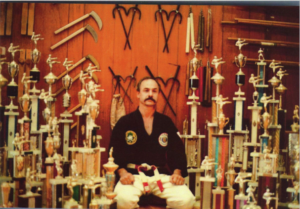

Again Gary and I started training on our own after the dojo closed. In 1968, I started teaching for the Department of Parks and Recreation in Washington, DC. I quit my full-time job in 1970 to open a dojo, “Shorin Karate Studios, Inc.” located in Silver Spring, Maryland, where I started teaching classes six nights a week, with private lessons during the day. Ever since leaving Okinawa, I’d been writing to Kise, but I could never get enough money to move him and his family to the United States, as I had hoped to do.

Kise had promoted me to Fifth Dan in 1967 after I’d been studying my Fifth Dan kata and techniques for three years. I was always looking for another teacher, but I couldn’t find anyone good enough in my mind, and I didn’t want to bastardize my training. I didn’t want to learn anything other than the style of karate Kise and Soken had taught me. Learning another style would make me a jack-of-all-trades, but master of nothing. Knowing about other systems is good—that’s why Kise took me to other schools on Okinawa—and being familiar with other styles is most helpful when you have to fight someone who has trained differently. But learning about various techniques is not the same as training in different styles or systems. To know and concentrate in depth on one style is always better than diluting your style by cross-training in multiple ones.

Training by myself for many years left me with nothing new to learn. In a way, that turned out to be a good thing: I concentrated on reinforcing everything I already knew. I gained a clearer understanding of the techniques; and learned how to deliver them with maximum speed, weight transfer, and strength. My knowledge of karate from day one had always been focused on building the foundation—that’s what Kise had taught me, and that’s what we’d always done. A stronger foundation can support a taller building. Training by myself taught me the true secret of karate: basics and practice, practice, practice. I began to understand completely how the essence of karate is created by the foundation of basics. Every move in a kata is also included in a basic drill somewhere. A fighter either has been taught it and knows it, or isn’t high enough in rank to have figured it out.

As head of my own dojo, I led my classes through the basic drills over and over again, just like we had trained in Okinawa. One training session could mean thousands of punches, blocks, and kicks, in every progressive permutation I could imagine. I worked my students until people were cramping up, and their arms and legs were bruised and swollen. I’ve never believed an instructor should stand around barking orders, so I did everything I asked of my students. If they did 1,000 front kicks, I did 1,000 front kicks. When my students sparred, I sparred.

In 1972 Grand Master Hohan Soken (his first and only trip) and Master Fusei Kise made their first trip to the States. I was finally reunited with my only instructors after eight years of training on my own. In 1974, Kise came to the US and stayed with me for several weeks. We worked out every day together for the first time in eight years. It was a great awakening for me. Kise had been a Fourth Dan under Maeshiro’s Shorinji-ryu when I first started karate back in 1960. Kise said he started training under Soken in 1954-5?.

In 1967 I found out that Kise had simply thrown out all that hard karate that he had and solely focus on Soken’s Matsumura Seito Shorin-Ryu. He no longer trained in the old hard system of Shorinji-Ryu. Kise couldn’t even remember any of the Shorinji kata. He didn’t remember or know the Shorinji version of Seisan, Wansu, or Anunku—the very first kata he had taught me. “This is Shorinji, and this is Matsumura. It is much better,” he explained to me. During all the time I’d worked out with Soken and Kise in Okinawa, I’d never heard those terms used. “Matsumura Seito,” Kise just said, “its upper-level Shorin-Ryu.”

In 1974 Soken and Kise appointed me as “US head of SMOKA ” (Shorin-ryu Matsumura Karate Association). Since I was heading the association, I interacted with a lot of Kise’s students after they returned to the US, both prior and after his complete change from Shorinji to Matsumura. These were senior ranks, like Fred Sypher, who had studied under Kise on Okinawa for six to eight years total time—much longer than I had. They practiced pure Matsumura, without any Shorinji. They used open hand techniques and a lot of body change, but they lacked the power that came from Shorinji-Ryu.

I was aware of those people and their karate when Kise and I started working together again. We trained together privately during the day, and he taught my classes in the evening. He was still strong, but not like he had been when I was on the island. He had more flash, and it was all body change.

During our time together on Okinawa, Kise would attack whatever came at him with a lot of aggressive contact and power. This was no longer his way.

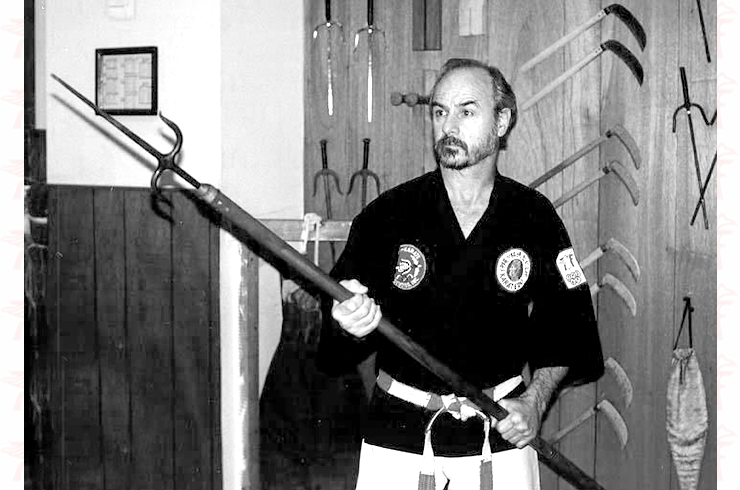

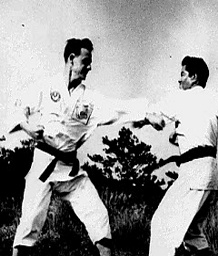

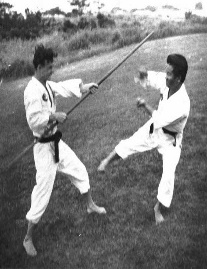

Free sparring with Kise on Okinawa Weapon fighting with Sensei Kise and Jimmy fighting with weapons It had been power, power, power—block hard, punch hard, and destroy. He could hit a guy hard enough to knock him to the floor, or simply break what he struck, but he wasn’t doing that anymore. His fingers and fists were still conditioned and hard enough to hurt you, but now it was about getting the body out of the way and letting the attacker impale himself on your strike.

Working with him again was great. After eight years of training the same thing over and over, I was finally learning something new. I could look at Kise’s teachings like they were a set of blueprints, and use them to envision the house. I could see that Matsumura had such potential, but only as an upper level of what I already knew. Kise taught me all the new Matsumura kata, as well as going over the ones I already had learned while on Okinawa. I refused to stop practicing the Shorinji and Soken versions of kata I’d learned on the island. Both Kise and Soken agreed that I should continue teaching both Shorinji and Matsumura.

I was trying to figure out how and why it worked so well for Kise, who was smaller than me and could handle big people with ease. I started comparing the Matsumura body change to a swinging barroom door. I also recognized aikido-style moves within the Matsumura, except—instead of throwing—we hit and impaled. I came to see Matsumura simply as the advanced stage of the Shorinji I had learned while on Okinawa.

Kise had changed; he didn’t care whether or not anyone else could make it work. He was using students as guinea pigs. In the late 1960s, (66’ to 69’) he started sending students back to the US who were trained to spar from a position of hands open—one up and one down low around the hips, with their bodies facing fully forward and the feet running parallel facing forward. I realized he was also trying to figure it all out and was in a transitional stage until he could learn how to do it properly. His students were getting their asses kicked, but Kise needed them as a sounding board in order to teach himself. He had them stand in certain ways and watched them learn from their mistakes. None of the guinea pigs could see how they were being used.

When Kise left to return to Okinawa, he told me: “You forget nothing.” He also warned me, however, that I was “driving my students.” away by training so hard.

The association continued to grow, so Kise returned to the US every summer for the next three to four years. We trained privately together, working on kata, drills, techniques, and weapons. In 1976, I hired a Japanese translator, Mrs. Ichikawa, because I didn’t want to misunderstand anything. One day, the translator turned to me and said: “I don’t know why you’re messing with this man, He hates you. He hates all Americans.”

That’s when things really started to fall apart, as I began to realize Kise was all about money. At first, I tried to justify it, telling myself how he had two kids in college; how things are more expensive on Okinawa; how he’s trying to make a living.

I understood how he might have felt putting so much time into an individual, just to have them move away. Kise probably looked at it as: “I put all this time into Jimmy, and he just went away”. They all promise they’ll bring me back and send me tribute, but none of them do it. Now they’re all gone and leaching off of me. Each and every year I had sent Kise money on his birthdays and the Holidays. Each of us in the US had told him the same thing for years, so I thought maybe he’d simply grown cynical.

The worst was that he even started trying to teach bullshit to me. I was totally immersed in figuring out the Matsumura when, around 1977, Kise started teaching grappling, arm-twisting, and submission techniques to us. It ran counter to my experience in fights and everything he’d ever taught me, so I disagreed with it completely. I had one student who was extremely strong—he could curl hundreds of pounds and catch me by the gi with one hand and lift me straight off the ground with that one hand. There was no way I could twist his arm or wrist to break away from him, no matter how skilled my technique.

If I get into an altercation, I’m going to hurt you, punch your lights out, or hit you in the eyes, attack the groin, etc. do any and everything needed to win. It seemed a joke to stand still and let a person walk up and grab you, planning to respond by twisting their wrist into some submission hold.

Kise had told me so many times for years: in the time it takes to catch someone, you can hit them, what would you rather do? I got so frustrated that I finally decided to push Kise to the limit and see what he’d do.

In late 1977, a few of us were in my dojo with Kise as he was teaching me a block and strike technique that I knew would get me hurt on the street. Kise was standing so close to me that I knew I could hit him long before he could block me. I just knew it. Back on the island in the 1960s, he never would have stood so close to me. I told him, “This is bullshit! This will get me hurt!”

I had a student named Tom Cochran, one of my black belts, standing to my right, and Kise was to my left. I turned to Cochran and said, “I don’t care what he does with his hands, look at his feet. Don’t take your eyes off his feet.”

Then I just turned and hit Kise as hard as I could in the chest—so hard it knocked him to the floor. As he jumped up, I came at him again, getting closer and closer. “Make it work,” I yelled at him. “Make it work!”

“Pretty soon I’m going to hurt you,” he seethed.

“Make it work,” I yelled. “Make it work from here,” I said, closing the gap. But Kise kept moving back to a control distance, instead of being in contact range. If I could reach out and touch him, I knew I was fast enough to hit him. Karate is a fighting art, not a sport, and I wanted to learn and teach it that way. Training has to be as practical as possible without doing any serious damage to the students. I do believe in students getting bruised and having the breath knocked out of them. Without contact, karate becomes less real and more a fantasy, erasing the connection between the dojo and the street. It’s an instructor’s job to guide students to a level of proficiency that enables them to defend themselves against a real attack on the street. That can’t be done without contact; it can’t be done slowly; it has to be fast because that’s how it happens on the street. I looked at Kise and told him, “This is bullshit. I don’t want anything to do with you anymore.” I truly felt like I had lost my teacher. The Kise of old was gone!

When we were training on the island, it was all for real. Kise never said to hit him anything but hard, and was always complaining that students were too soft. It was always harder, harder, faster, more. When we were sparring, a student couldn’t even earn a point without knocking someone back or down. The new Kise was all easy, easy, not too hard.

I became convinced that Kise was teaching me bad karate. I didn’t know how he could expect me to buy into it when he had me stand in front of him so close that I could touch him without bending forward. Kise was just watering the system down. The thought gave me a really bad taste in my mouth that just grew sourer with time. Then one day I found out Kise had given a pack of fifty signed certificates to a regional rep without even telling me, and I was the Supreme Authority, on would think I was to be informed. After this guy called to announce he was in charge of the whole East Coast, I called Kise and asked, “Who’s this guy?” “I don’t know,” Kise said, “but he’s got a lot of students.” Once again it was all about the money.

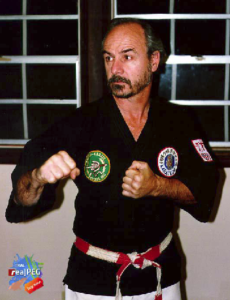

Kise promoted me to Seventh Dan in 1977 and gave me “Supreme Authority” over the entire United States for the association, but I didn’t want to be a part of it anymore. I’d had enough, so we went separate ways. I only wanted to teach real karate, and I didn’t care if I ever learned another thing or received another promotion.

In 1978, I parted ways from Kise, the same year, Soken stopped being his teacher, and it has been more than forty-one plus years now that I’ve been on my own again. I’m still teaching and working on perfecting the system—still examining all of my own kata, which has become clearer to me over the years. I closely examine each hand position and block, questioning whether, for example, a certain move covers and protects exactly what it should. I work on clarifying moves, looking at how one movement or hand position covers several things.

The street application of everything has become more important to me than sparring.

In the end, even though I broke with Kise, karate has been “THE” stabilizing factor in my life. It gave me the confidence and balance to achieve success. At times I have felt like I wasted too much of my life on karate—time I could have spent in college getting a degree that could have earned me more money. Yet I feel like I earned my doctorate in karate, and that is something very few can say. Through the course of my 58 plus years of teaching, I have had students of a very high education that was very wealthy and successful. I have trained the complete span of Doctors and Lawyers to Police Officers and other highly skilled professionals. I am their teacher and have earned their respect—something I could never have gotten without karate. I have been professionally successful, with plenty of fancy cars, a big home, and even four airplanes—none of which I would have had without karate. Without it, I most likely would have ended up in jail, just like the guys I ran with during my youth. Instead, I have had and still have direction and focus, which all came from karate.

Kise and Master Soken are the only two karate instructors I have ever had, or ever will have. I will remain a 7th Dan for life, I will not sell out my Art.

I am forever indebted to Sensei Kise for the training he gave me. I love him like a brother and will always respect him for his incredible knowledge and skill.

The Kise of “OLD” will forever have my respect.